Government Shutdown: 1995, 2013, 2018, and 2019

The Balance / Caitlin Rogers

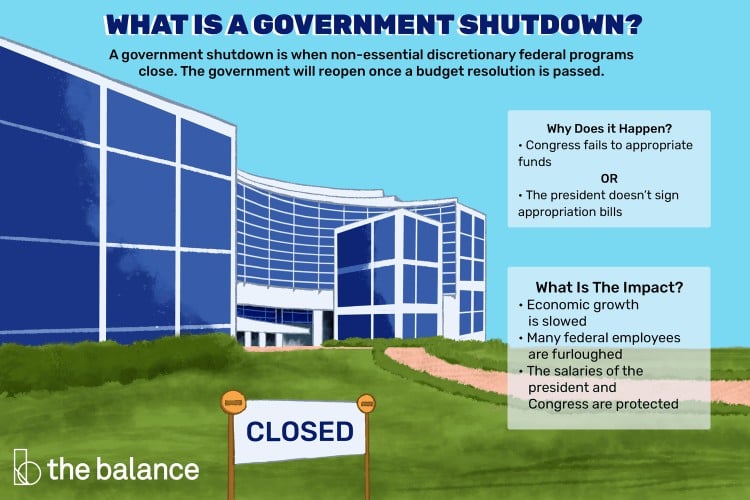

A government shutdown is when non-essential discretionary federal programs close. It occurs when Congress fails to appropriate funds or the president doesn’t sign the appropriations bills.

Note

A government shutdown is different from a debt ceiling crisis. The first occurs when Congress hasn’t appropriated funds. The second occurs when Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling. The U.S. Treasury Department cannot borrow above the debt ceiling. In both cases, government agencies don’t have funds to operate. In the second, Treasury also cannot pay holders of Treasury securities, and the United States defaults on its debt.

What Happens During a Government Shutdown

The discretionary budget funds most federal departments. When Congress doesn’t appropriate funds, these departments must close unless they have surplus funds.

Note

During a shutdown, many federal employees are furloughed. That means they are sent home without pay.

Employees that provide essential services may be required to work without pay. Essential services are those that include national safety and security. All workers receive back pay once funding is approved.

Many agencies that provide essential services are set up so they can operate for weeks without a funding bill. U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Federal Emergency Management Agency, Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the Transportation Security Administration remain open. Many functions of the Department of Justice have their own source of funds. The Postal Service has a separate source of funds, so mail continues to be delivered until that source of funding is exhausted.

Note

The Constitution protects the salaries of the president and Congress during a shutdown.

Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid payments are part of the mandatory budget. Mandatory programs are rarely shut down because their funding is automatic. They were created by prior acts of Congress.

Here’s an example of the impact on the major departments from the 2018 to 2019 shutdown. It includes how the percentage of workers who were furloughed, where available:

- Agriculture: 43.5% of workers.

- Commerce: 31.5% of workers. Reports from the Bureau of Economic Analysis were delayed. The National Weather Service continued providing forecasts.

- Education: Public schools remained open. Many employees were furloughed.

- Energy: Oversight of the safety of the nation's nuclear arsenal and nuclear energy sites remained in place.

- Environmental Protection Agency: 92.9% of workers.

- Food and Drug Administration: 29.4% of staff.

- Health and Human Services: 24% of staff.

- Homeland Security: 13.1% of workers.

- Housing and Urban Development: 86.7% of workers.

- Internal Revenue Service: Most services shut down.

- Interior: 82.9% of workers: National parks, museums, and monuments were closed.

- Justice: 15.9% of workers.

- Labor: 77.7% of employees. Most activities shut down, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics and worker protection investigations.

- NASA: Staff that support the International Space Station remained employed.

- Smithsonian: All museums were closed. Employees that care for National Collections, such as animals and archived materials, remained employed, as did security staff.

- State: No employees were furloughed.

- Treasury: About 42% of workers.

Impact on the Economy

A shutdown slows economic growth. One reason is that federal government spending is itself a component of gross domestic product. It contributes about 7% of economic output. A second reason is that workers and contractors who don't get paid spend less. That creates a multiplier effect that gets worse the longer the shutdown continues.

For example, the 2018 shutdown reduced GDP by $11 billion. That’s $3 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018 and $8 billion in January 2019. The true cost of the shutdown is probably higher. The Congressional Budget Office couldn't estimate the impact on businesses that couldn't get federal permits or loans in time.

Recent U.S. Government Shutdowns

Before 1980, funding gaps occurred but they rarely led to shutdowns. Agencies assumed Congress meant for them to keep working, so they did. But U.S. Attorney General Benjamin R. Civiletti issued two opinions that required agency heads to suspend operations until Congress appropriated the funds. Only essential functions or agencies that had the funds could continue.

The longest shutdown lasted 35 days from Dec. 21, 2018, through Jan. 25, 2019. A 16-day shutdown began on Oct. 1, 2013. Two brief shutdowns occurred in January and February 2018.

2019

The government began the year in a shutdown that had started in 2018. It lasted until Jan. 25, 2019.

2018

The first shutdown of the year began on Friday, Jan. 19, 2018, when the government closed down for almost three days. The U.S. Senate failed to pass a continuing resolution to extend spending until Feb. 16, 2018. The resolution was a stopgap measure to buy time to pass the budget for fiscal 2018.

On Jan. 22, Congress ended the shutdown. It passed a continuing resolution that expired at midnight on Feb. 8, 2018.

On the morning of Feb. 9, the government shut down again, this time for only a few hours, until the president and Congress could pass another continuing resolution.

The third shutdown began on Dec. 22, 2018. It lasted 34 days, until Jan. 25, 2019. It delayed $18 billion in discretionary spending. It reduced economic output by $11 billion: $3 billion in the fourth quarter of 2018 and $8 billion in the first quarter of 2019.

2013

The shutdown went on from Oct. 1 to Oct. 17, 2013. Around 850,000 employees, or 40% of the federal civilian workforce, were furloughed. Reduced government spending lowered GDP by 0.3%.

Republicans used the shutdown to try to stop the launch of Obamacare. The Republican-controlled House submitted a continuing resolution that lacked the funds to administer the Affordable Care Act of 2010. The Senate rejected the bill and sent one back that funded the program. The House ignored that bill. It sent one back that delayed Obamacare’s implementation. The Senate ignored that bill and the government shut down.

Ironically, the shutdown did not stop the rollout of Obamacare. A large portion of its funding is part of the mandatory budget, just like Social Security and Medicare. The Department of Health and Human Services had already sent out the funds needed to launch the health insurance exchanges.

The Obama administration reported the shutdown slowed economic growth by 0.2% to 0.6%. It also cost 120,000 jobs. Around 850,000 federal employees were furloughed each day.

1995

The government shut down twice: Nov. 13 to Nov. 19, 1995, and Dec. 15, 1995, to Jan. 6, 1996. In the first shutdown, 825,000 federal employees were furloughed. During the second shutdown, 284,000 federal employees were furloughed. In the second shutdown, fewer workers were furloughed because Congress had passed some appropriations bills. Other workers were called back without pay because the positions were reclassified as critical.

The two shutdowns cost $1.4 billion, according to the Office of Management and Budget. That’s worth $2.4 billion today. In addition, 480,000 emergency employees, including prison guards, medical personnel, and FBI agents, worked without pay. At least 170,000 veterans missed their monthly education benefits. Over 200,000 passport applications were held up. More than 7 million National Park visits, and 2 million museum visits, were prevented.